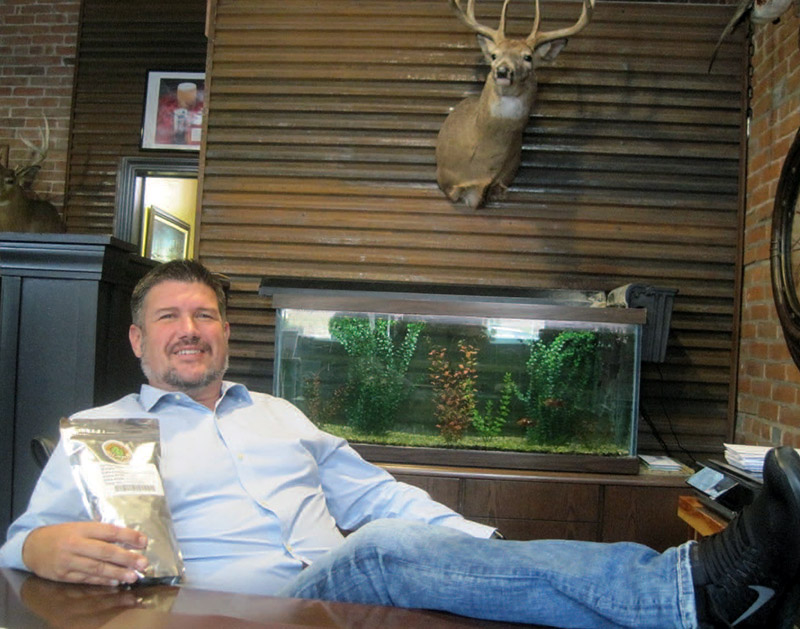

Mark Pattison of Buck Creek Hops shows off a package of frozen hops ready for distribution to brewers at his Solon office. A pound of processed hops costs about $15. PHOTO DAVE DEWITTE

By Dave DeWitte

dave@corridorbusiness.com

A large stream of economic potential from Iowa’s craft beer boom – the local sourcing of beer ingredients – is still waiting to be tapped.

The number of Iowa breweries doubled from 34 in 2012 to 70 in 2016, according to the nonprofit Brewers Association. It ranks Iowa 14th among states in brewery density, with 3.2 breweries per 100,000 adults over 21, and estimates its economic impact at more than $860 million.

Yet brewers continue to source their hops, barley and even oats from other states because sources in Iowa are extremely limited and prices higher.

That situation is changing, however, as prices of the state’s two main crops, corn and soybeans, remain in a depressed state. A leading force for that change can be found in the heart of the Corridor.

Buck Creek Hops in Solon began growing the plant in 2014 and last year expanded production to about 20,000 pounds of hops. It added a facility for pelletizing and packaging hops and has a thriving consulting business with farmers and landowners planning to diversify into the crop. It contracts to buy hops from other growers, and even offers custom services, which include developing hop plots and harvesting.

“Our goal is to bring a more quality hop to the small to medium-sized brewer that they don’t have access to now,” said Mark Pattison, who started the venture with partners Chad Henry, Dan Paca and Lee Pattison.

Buck Creek’s biggest regular customer is Millstream Brewing in Amana, which helped pioneer the current wave of craft brewing in the state, and Mr. Pattison can count on testimonials from Head Brewer Chris Priebe. Mr. Priebe says the fresh local hops have a brighter, more poignant taste than more commonly sourced Cascade hops from Washington’s Yakima Valley.

“Hops are the most interesting thing to get locally,” Mr. Priebe said. “They’re a little like grapes. Their flavor is regionally different.”

Millstream’s biggest seller is a India pale ale called Iowa Pale Ale, “so it makes sense to source the hops from Iowa,” Mr. Priebe added.

Buck Creek Hops charges more for its hops than the big producers – about $15 per pound – which can be partially offset by lower shipping costs. Unprocessed hops commonly sell for $6-$12 per pound, which can sound attractive to farmers who are now getting about $3.40 per bushel for corn and $9.80 per bushel for soybeans.

More and more farmers are growing hops, according to Iowa State University Assistant Professor Diana Cochran, who leads ISU’s fruit crop and hop research program, and has a one-acre hop test plot. She counts 30-40 existing hop growers in the state and two growers’ alliances – one organized by Buck Creek to help educate and support growers and the other in northwest Iowa.

Most growers are far smaller than Buck Creek’s 55 acres and only grow plots from one-half to five acres. More and more landowners want to give it a try, however.

“I get at least one or two calls per week from someone who’s interested,” Ms. Cochran said. “It can be up to five calls.”

That’s understandable, considering hop prices and demand remain strong. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that domestic hop production rose 11 percent last year, but the value of the crop rose 44 percent to $498 million, as more acreage was shifted to Aroma varieties that bring higher prices per pound.

If few Iowa brewers embrace homegrown hops, Ms. Cochran says it might be because the craft brewing industry in the state remains in its infancy, relatively speaking.

“The issue I see is the brewers are very interested, but they, too, are building their business,” she said. “While they have equipment to brew the beer, doing the experimental batches to see how they can brew with the hops growing in Iowa is a different thing. They don’t all have the small-batch equipment.”

Buck Creek contracts with emerging hops growers from Sioux Falls, South Dakota, to Galesburg, Illinois, to supply it with hops. The company also contracts with growers in the Corridor, including a 15-acre operation near Shueyville, and a 10-acre operation under development near West Liberty.

Great hop-portunities

Mr. Pattison said there’s a reason not every farmer is jumping into hops, despite the good prices and skyrocketing demand.

Developing a hops operation can cost $15,000 an acre between planting and constructing the trellises required to support the vining plants. Producing crops also involves a lot of manual labor.

“Eighty percent of the people who contact us, once they see they labor involved, they are out,” Mr. Pattison said.

The hops vines take three to five years to reach full maturity and productivity; in the meantime, the plants can fall victim to fungus and diseases due to the heat and humid conditions of Iowa summers.

Buck Creek hired Christian Peterson, an ISU-educated horticulturist specializing in hops, and invested in an expensive German-made Wolfe harvester, a sort of combine for harvesting the vertical crop that reduces the labor burden. Mr. Pattison said Buck Creek also has the ability to tap the resources of his commercial development company, North Corridor Properties Investments, including heavy equipment and labor to develop new plots.

The first few years of Buck Creek Hops have been a ramp-up, Mr. Pattison said. He expects the company to achieve profitability within the next year, as production gets closer to full capacity. Buck Creek is entertaining an expansion into barley, a beer ingredient that can be used as a winter cover crop. It doesn’t have the profit potential of hops, Mr. Pattison noted, but “we’d be able to become a one-stop shop” for brewers.

Ms. Cochran said Michigan offers a model for hops cultivation in a harsh Midwestern climate, and an ISU workshop series plans to offer a five-day tour of Michigan’s hop-growing industry this fall. One thing that state offers that Iowa so far lacks are hops-grower cooperatives, which allow growers to pool their resources on things like processing, palletizing and packaging equipment, to help them market their products together.

Growers in the Northwest states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho dominate the nation’s hops production. Washington state grows 75 percent of the nation’s hops, with the leading varieties being Cascade, Simcoe, Zeus, Centennial, Citra and Mosaic.

Hops are roughly divided into two categories: bittering hops, which give beer its characteristic bitter edge, and aroma varieties, which give it more complex flavor characteristics. Craft brewers are increasingly buying larger volumes of aroma varieties, some of which cannot be grown in Iowa because they are patented by grower groups in the Northwest, Ms. Cochran noted.

Iowa’s climate and soils can grow some of the popular aroma varieties, however. ISU’s test plot includes Cascade and Chinook varietals, as well as trials of eight cultivars to determine which thrive best in Iowa conditions.

Most Iowa craft brewers have some kind of relationship with a local farmer, “if only to haul away the unused spent grain” from the brewing process, according to J. Wilson, coordinator of the Iowa Brewers Guild. He said brewers locally source a variety of flavoring ingredients, including honey, aronia berries and even mushrooms.

“I’ve done carrots, beets and cucumbers,” said Mr. Wilson, an amateur brewer. “Peace Tree [a craft brewery in Knoxville] does Cornucopia, a saison made with sweet corn.”

Lion Bridge Brewing Co. in Cedar Rapids sources local honey from Indian Creek Nature Center and maple syrup from Great River Maple in northeastern Iowa as flavoring ingredients, owner and brewer Quinton McClain said. This fall, Mr. McClain used 200 pounds of cucumbers from Bass Farms near Mount Vernon to brew a batch of cucumber ale. For main ingredients, however, Mr. McClain said it’s still a challenge to go all-Iowa.

“Hops, if you want to go all-Iowa, you could,” Mr. McClain said. “A few people have inquired with us about switching their farms over to growing oats or barley. I don’t know if any of them have followed through.”

Mr. Pattison, himself a brewer, is confident that Iowa growers can succeed with hops. Whether craft brewing demand will extend to other crops from Iowa is less clear to the grower, but he’s excited by the role Buck Creek Hops is playing.

“I love entrepreneurship,” Mr. Pattison said. “We brought a whole industry to the state of Iowa. We didn’t start a business – we started an industry.”