Protesters hold a mini-protest at the Iowa Statehouse calling for a $15 minimum wage during Gov. Kim Reynolds’ Condition of the State address on Jan. 9. PHOTO PAT RYNARD

By Katharine Carlon

katharine@corridorbusiness.com

Ed. note – This is the final part in the CBJ’s “Working for a Living” series exploring wages, affordable housing and cost of living in the Corridor. Read the first two parts here and here.

A livable wage means more than keeping the lights on, being able to afford the occasional splurge or living in dignity without having to resort to social programs. For advocates of a higher minimum wage like Greg Hearns, president of the Iowa City Federation of Labor, it can mean the difference between safety and putting workers – and their children – in extreme jeopardy.

“When it comes to choosing whether or not you’re going to have child care, whether or not you’re going to pay your rent, whether or not you’re going to have food, I’ve seen situations where people chose to leave their kids home alone while they went to work on second and third shift,” said Mr. Hearns of some of the shift workers he represents. “I think that’s a tragic commentary.”

Mr. Hearns’ comments followed a vote by the Johnson County Board of Supervisors late last month to increase the county’s recommended minimum wage by 17 cents to $10.27 an hour beginning July 1. The vote was purely symbolic – the Iowa Legislature last year overruled Johnson, Linn and three other counties that had enacted higher minimum wages, and current legislators have shown no appetite to visit the issue on a statewide level.

Although it’s down, the minimum wage issue is far from dead, supporters say, with gestures like the Johnson County vote helping keep the flame alive. Organizers across the Corridor continue to agitate as the gap between wages and the cost of living increases. Many believe that political winds are shifting quickly and could bring dramatic change to Des Moines next year. Meanwhile, market forces – particularly the region’s nearly non-existent unemployment rate – are driving up wages, with or without legislation.

“Symbolism is powerful and meaningful,” said Stacey Walker, a Linn County Supervisor and long-time supporter of higher wages, adding that he commended Johnson County’s action. Although Mr. Walker said he wasn’t sure Linn County would follow the lead of its neighbor to the south, he and partners at Living Wage Linn County, which helped push through the county’s $10.25 minimum wage ordinance before it was overturned, plan to continue urging businesses to voluntarily pay higher wages while strengthening support for a livable wage statewide.

Mr. Walker said he expects the minimum wage to become a major issue in the upcoming gubernatorial and state races, which could have major repercussions if a “blue wave” materializes in November. Democratic primary candidate Cathy Glasson of Coralville has called for a statewide increase to $15 an hour. So has Nate Boulton, of Des Moines, who also advocates linking the minimum wage to the Consumer Price Index – the same mechanism that prompted Johnson County’s 17-cent raise.

“People need a living wage to live with dignity and raise a family,” Mr. Walker said. “Part of the American promise is that if you find a good job and are a good worker, you have the right to be able to earn a wage that can support you. You shouldn’t have to draw on social benefits to live in dignity. The most compelling reason is here in America, we constantly hear if you work hard and play by the rules you can access that American dream and get ahead.”

The wage environment

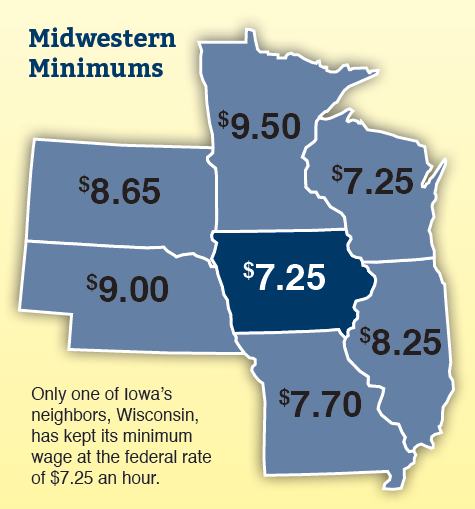

Iowa’s statewide minimum wage of $7.25 an hour is lower than all neighboring states except Wisconsin, placing it in the minority of 21 states nationwide with wages set at or below the federal rate. Enacted 10 years ago, the state wage is less than half the $15.06 an hour each working parent in a family of four must earn just to get by in the Cedar Rapids area, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Living Wage Calculator, and well below the $17.63 an hour each parent would need to earn in and around Iowa City.

Wages in the Corridor have ticked up somewhat after years of stagnation, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data showing the average take-home pay increased more than 3 percent in both Johnson and Linn Counties between the second quarters of 2016 and 2017.

Wages in the Corridor have ticked up somewhat after years of stagnation, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data showing the average take-home pay increased more than 3 percent in both Johnson and Linn Counties between the second quarters of 2016 and 2017.

A study conducted for the Johnson County Board of Supervisors by Peter Fisher of the left-learning Iowa Policy Project and University of Iowa Economics Professor John Solow on the impact of the county’s 17-month experiment with an enforceable higher minimum wage suggested that not only had it not harmed local business, but that earnings growth for workers in he traditionally low-paid leisure and hospitality sector saw a nearly threefold increase between 2015-2017.

But the cost of living in the region has also increased, Mr. Fisher told the CBJ earlier this year. Rents went up 11 percent in Johnson County and 7 percent in Linn County in 2017. Child care costs jumped 3 percent in both counties, compared to just 1 percent statewide.

“I doubt the people in Des Moines know how to live with $7.25. They don’t know that; that’s why they went ahead and did this,” Iowa City Council Member Mazahir Salih said of the legislature and then-Gov. Terry Branstad’s decision to strip Iowa jurisdictions of the ability to set a minimum wage. “If they really knew the people who suffer even to spend time with their kids.”

Ms. Salih, an activist and co-founder of the Eastern Iowa Center for Worker Justice, said the minimum wage issue impassions her because she’s lived it.

“I came to this country in 1997 and, as any immigrant, I had to start all over, and I started by working at McDonald’s,” she said. “I worked as a cashier at McDonald’s and they paid me $5.25. … Twenty-one years later, the minimum wage is still $7.25. Who can believe that? This is ridiculous.”

Michelle Hoehne, community coordinator for the Center for Worker Justice, said even though the minimum wage effort is dormant at the state level, the organization has collected commitments from around 160 Johnson County businesses to honor the countywide minimum wage. Devin Mehaffey of Living Wage Linn County said his group is doing the same in the Cedar Rapids area, in addition to reaching out to lawmakers, lobbying them to raise the minimum wage and restore local control.

“I think these campaigns do a lot in keeping this issue alive in the community’s mindset,” Mr. Mehaffey said, adding it was surprising how many businesses continue to pay just slightly over minimum wage despite a stressed labor market. “It’s important to educate and encourage businesses to pay a living wage, which in this area is about $14 an hour to meet basic needs.”

Ms. Hoehne agreed, adding she believed many of the Johnson County businesses that have signed up so far “truly believe in these values and want workers in this area to have a living wage.” Beyond mere altruism, she said, businesses have trouble recruiting workers without paying wages comparable to their competitors, not to mention the fact that higher wages are a form of economic development.

“When workers have money in their pocket, they’re more likely to spend that money,” Ms. Hoehne said. “If every penny is going for rent or for groceries, they’re certainly not shopping or eating downtown.”

“Those dollars get reinvested in the community,” echoed Mr. Walker, who said higher wages also promote higher productivity and less turnover.

Differing viewpoints

When Johnson County’s new minimum wage kicks in this summer, Oasis Falafel – one of the many restaurants, shops and other businesses that committed to $10.10 last year – will raise its starting pay as well. Co-owner Ofer Sivan said it was barely a question for he and partner Naftaly Stramer.

From a purely pragmatic point of view, Mr. Sivan said, there’s little choice in a region where unemployment has hovered at or below 2 percent for months, making it one of the tightest job markets in the country – one where employers compete fiercely via benefits, bonuses and better pay than the guy next door.

But more than that, he said, “It’s the right thing to do. The federal minimum wage is not in line with reality. You could even say it’s unethical.”

Aaron Vargas, general manager of Backpocket Brewery in Coralville, also said his business signed on because it was the right thing to do.

“We thought they deserved it,” Mr. Vargas said. “We had good people and we wanted them to stick around. If we had dropped down [after the increase], we would have had much higher turnover. That’s just how it is. There are a lot of options for people to get a higher wage in this area and we have to be competitive.”

Mr. Vargas said Backpocket hadn’t yet made an official decision to increase all starting wages to $10.27, although he said that the large majority of is employees already make above that mark with the exception of tipped employees.

Not all Corridor business owners agree with the philosophy of a moral imperative for higher wages, however. Jessica Croskey, the general manager of Wendy’s on Collins Road in Cedar Rapids, advertises entry-level wages of $8.25 on Indeed. com – an appropriate wage, she said, for workers with no experience in an industry wracked with turnover. Ms. Croskey said she preferred to reward those employees who perform well and remain on the job past 90 days with pay hikes and perks.

“I don’t like to start people off at minimum wage because I don’t think they can live on it,” she said, adding that, on the other hand, “It’s not really about the wage. It’s that nobody, or very few people, want to work and that’s the real issue for any business in Cedar Rapids. I don’t think bumping up pay would make any difference. In my experience, a lot of people find it optional to show up on time; they want to play ‘create your own schedule.’”

Ms. Croskey said for every 10 people she hires, about two stick around beyond the 90-day review mark: “Those are the people I want to reward. We have a point system based on dependability, attendance, job performance. I want to pay higher wages that people can live on, but you have to want to work.”

Michael Saltsman, managing director of the Employment Policies Institute, a conservative D.C. think tank that lobbies against the minimum wage, said he believes managers and business owners should be free to decide – or let the market decide – what wages they should pay. Mr. Saltsman said he has watched the situation in Johnson County with keen interest, and called the supervisors’ recent action “a symbolic, virtue-signaling step up” that was likely to have a negative impact on employers and lead to businesses shutting their doors.

“It’s a public relations charade and a waste of taxpayer money,” he said, pointing to one statistic not highlighted in Johnson County’s recent minimum wage report: BLS data suggesting that after five years of steady growth in the restaurant industry, 2016 – the year the wage increase was imposed – found new restaurant employment in the county grinding to a halt.

“They trotted out researchers to put together a report telling the Johnson County Board of Supervisors exactly what they wanted to hear,” he said. “This report looked at broad topline numbers to show Johnson County is doing great – or at least didn’t fall off a cliff.”

In a written response to Mr. Saltsman, Mr. Fisher pointed out that the growth rate in restaurant jobs fell by an even greater percentage across the state of Iowa in 2016, including in the comparison counties of Linn, Story and Black Hawk.

“Unfortunately for Mr. Saltsman’s critique, the actual story for restaurants in Johnson County is the same as the story we found for the larger hospitality sector, which includes bars, hotels and motel,” he wrote, adding that average weekly earnings at restaurants after the minimum wage increase rose by at least three times the rate for the period preceding the increase, and at a much higher rate than the state as a whole.

“Unfortunately for Mr. Saltsman’s critique, the actual story for restaurants in Johnson County is the same as the story we found for the larger hospitality sector, which includes bars, hotels and motel,” he wrote, adding that average weekly earnings at restaurants after the minimum wage increase rose by at least three times the rate for the period preceding the increase, and at a much higher rate than the state as a whole.

Mr. Fisher noted that the number of restaurant jobs and eateries continued to rise in Johnson County, as did the number of eating and drinking establishments.

Numbers aside, Mr. Saltsman said local increases were probably the worst option of all for lifting worker pay due to the “border” and “patchwork” effects of dramatic wage changes from one community to the next. The experience of the San Francisco Bay area, where local municipalities mandate wages ranging from $12-$15 an hour “within a short bike ride of one another,” is not just an administrative headache, he said, but a job-killing one that impacts the people it purports to help.

Targeted programs and tax breaks like the Earned Income Tax Credit are better vehicles for giving those in need a leg up, he said.

“We have to strike a balance between preserving jobs and targeting help to people who need it,” Mr. Saltsman said, adding it’s easy to portray those not supporting a higher minimum wage as heartless villains.

“Business owners having trouble attracting new talent are going to do it regardless. Imposing a wage gets it backwards, suggesting an ideological commitment when business owners don’t need people to tell them they have to pay more to get more applicants.”

Mr. Sivan of Oasis said he agreed that paying higher wages eats into profits that can be thin anyway, but his main issue is that making them a choice at all is unfair.

“It does add up, there’s no way around it,” he said. “It would be better and much fairer if everyone was required to do it and on an equal footing. Nevertheless, it’s still the right thing to do. Definitely, our payroll has gone up because of it, but it gives us a competitive advantage in the meantime.”

Official reaction

Johnson County Supervisor Kurt Friese said Johnson County’s experience is proof those predicting doomsday scenarios for businesses were off base.

“Naysayers, going all the way back to the ‘30s when the minimum wage was first proposed, kept saying this is going to destroy businesses and all these other complaints … and every single time it didn’t happen that way,” he said. “It ends up being a net gain for the community and yet they keep making the same argument – every time. The old anecdotal definition of insanity.”

Supervisor Janelle Rettig said the minimum wage hike had impacted 19,000 Johnson County residents and sparked a statewide discussion that isn’t going away any time soon.

“All of our data shows the minimum wage is working,” Ms. Rettig said. “It is raising wages for people in Johnson County. It did not impact revenue whatsoever, collections of hotel-motel or sales tax, or any of that. Our economy is growing. Our unemployment is lower than when we passed it.”

“This legislature and this governor will not be there forever micromanaging local government. It has never been what Iowa stands for and I bet we reverse course in the coming years.”

For Mr. Hearns, the union organizer, that’s a good thing.

“Not everyone can be represented by a labor organization, so that’s why this type of legislation is really important,” he said. “If employers always did the right thing, there would be no need for unions.”